Getting Comfortable With Our Monthly Flow

Like hitting the light switch when you walk into a room, you hit puberty as a female and then one day you wake up with your period. For some girls, from day one, it is regular like clockwork and for others it takes a bit of time before there’s a regular monthly bleed. I scratched the back of my memory to what my school health and PE lessons taught about the female period. It was focused on how to use a tampon and pad, and why menstrual bleeds occurred (i.e. the lining of the uterus was shedding). But other than that, not much else was discussed. At school we all knew we were at the age of getting our ‘flow’, ‘code red’, ‘period’, ‘*insert whatever nickname you have given it here*’, and that getting it was a sign of a healthy body. But how often was it discussed in regard to the young female athlete?

In the last few years, we have seen a massive shift in perspective of what defines a healthy female athlete. We are seeing more physiologists, coaches and athletes talking about their menstrual cycle. Females are learning more about their menstrual cycle and sharing this amongst their peers. This is beneficial in taking the steps needed to eliminate the taboo that exists around this topic and the awkwardness of asking for help or information. However, there seems to be a general train of thought that having a cycle is good and losing it is bad. My concern is that we have simplified this so much that we may miss the early signs of disruption to our physiology. Why are we only telling people to look out for when the ambulance has driven off the cliff and are not looking at tapping the breaks early.

The female reproductive system is an incredibly dynamic and adaptable system that goes through a maturation process in puberty, adapts to external and internal stressors in adulthood and regresses until menopause. We need to understand that the development and regression of the reproductive cycle in females is a bit more like a spectrum than a light switch. Viewing the reproductive cycle as a spectrum can help us identify the early warning signs of when things may not be ‘quite right’.

The first step of the menstrual cycle development is the increase in follicle developing hormones from the brain (hypothalamus and pituitary gland). These initiate follicle develop in the ovaries. This growing follicle will secrete oestrogen, which will start causing the endometrial lining in the uterus to thicken. When we first start having a period this is the first hormone that we produce. Sometimes we produce it at a constant rate and other times we produce large spikes in this hormone. The body is going through the initial phase of developing the follicular phase and starting exposure to the first reproductive hormone, oestrogen. We have a period at this point because we get the removal of oestrogen that results in the shedding of the endometrial lining and, as a result, flow comes to town. It may take time but soon our bodies will secrete consistent levels of oestrogen and then around days 10-14 of the cycle our bodies eventually produce a massive peak that helps to ovulate (the releasing of the egg from the ovary in the fallopian tubes). It takes some time for our body to initiate this ovulation process so the first few cycles occur without an egg being released into the fallopian tube. One very simple way to check if ovulation has occurred is to measure body temperature in the morning for 5 minutes before eating or exercising. If there is no change in body temperature throughout the cycle, then there is a good chance that there has been no ovulation.

After our body gets into the habit of ovulating, the final step in the menstrual cycle maturation is to develop a robust and sufficient luteal phase with high levels of progesterone (~days 15-28 of the textbook cycle). Progesterone in the female body causes changes such as increasing heart rate at rest and during exercise, and increases basal body temperature. It is a metabolically demanding hormone and research has suggested for females to maintain weight in luteal phase we naturally start eating ~200-300 kcal more a day in this phase. Again, it may take some time to develop a luteal phase that has high and sustained levels of progesterone in an appropriate balance to oestrogen (which drops to moderate levels in the luteal phase). Once this final piece of the menstrual cycle is developed then there is a fully functioning menstrual cycle. There are some researchers that have suggested to get to this point will take ~12 gynaecological years (ie how many years have you had a period for, if you start your period at 13 yrs of age and have no interruptions due to exercise or contraception then you should achieve this at 25 yrs of age).

As we mature and enter adulthood, we don’t just maintain a normal textbook 28-day cycle with no issues. If you have ever tracked your cycle you will notice sometimes it comes early, sometimes a day later and there is a huge amount of variability in your own cycle length and characteristics. This is because our cycle adapts to both external stress (extreme dietary changes, large increases in exercise training volume) and internal stresses (social, work and emotional stress). In cases of high stress, many females will have a luteal phase with low progesterone levels or even an anovulatory cycle. They may notice that their menstrual bleed is heavier than normal. This is likely due to high levels of progesterone countering the effect that oestrogen has in the endometrial lining and stops the continuous development and thickening. Without enough progesterone in the luteal phase we may be oestrogen dominant and have exaggerated endometrial thickening and heavy bleeding during ‘the time of the month’. What can then also be noted is that we have to regress through a number of steps before we ‘lose our cycle’. Which means there have been numerous warning signs telling you that something isn’t right. These could be a change in premenstrual symptoms, mood, sleep, heaviness of the menstrual bleed or a change in the length of cycle. The key in recognising these will come from regular tracking of your cycle so that you can monitor what is normal for you and if there is a deviation away from this that align with internal or external stressors.

We have an incredible and adaptive reproductive system that is a key indicator of physiological health. We need to be aware that it isn’t purely about having a cycle and or not having one. It is about understanding how our cycles responds to stress (external and internal) and then putting in place rest and recovery processes that help maintains a healthy physiology that ultimately will improve health and wellbeing.

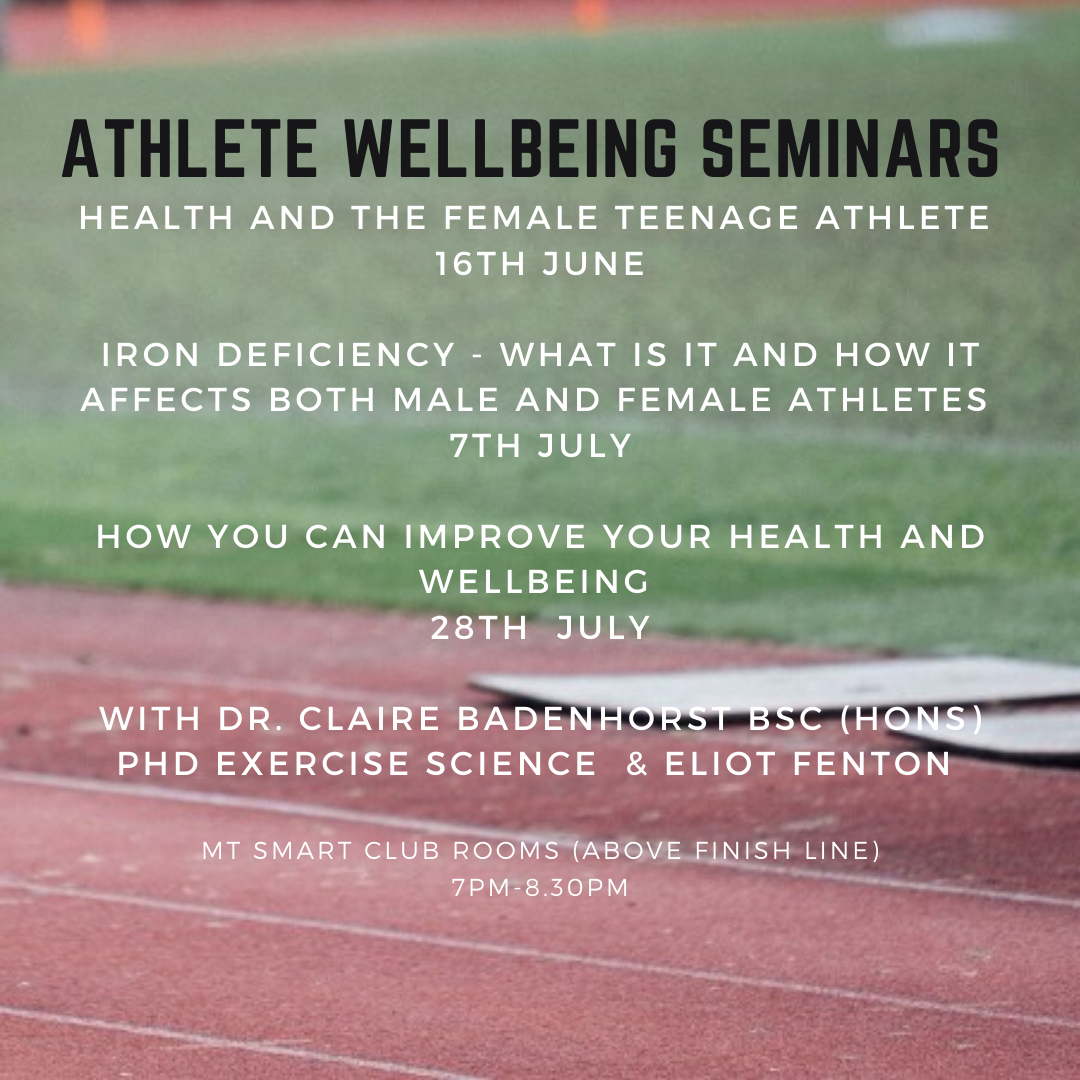

Dr Claire Badenhorst is a Sports Lab Physiologist and is presenting on female athlete health at the Athlete Well-Being Seminars co-hosted by Sports Lab and Auckland City Athletics. For event registration click here.